NOTE: In this post, I draw upon my experience and training as a secondary educator.

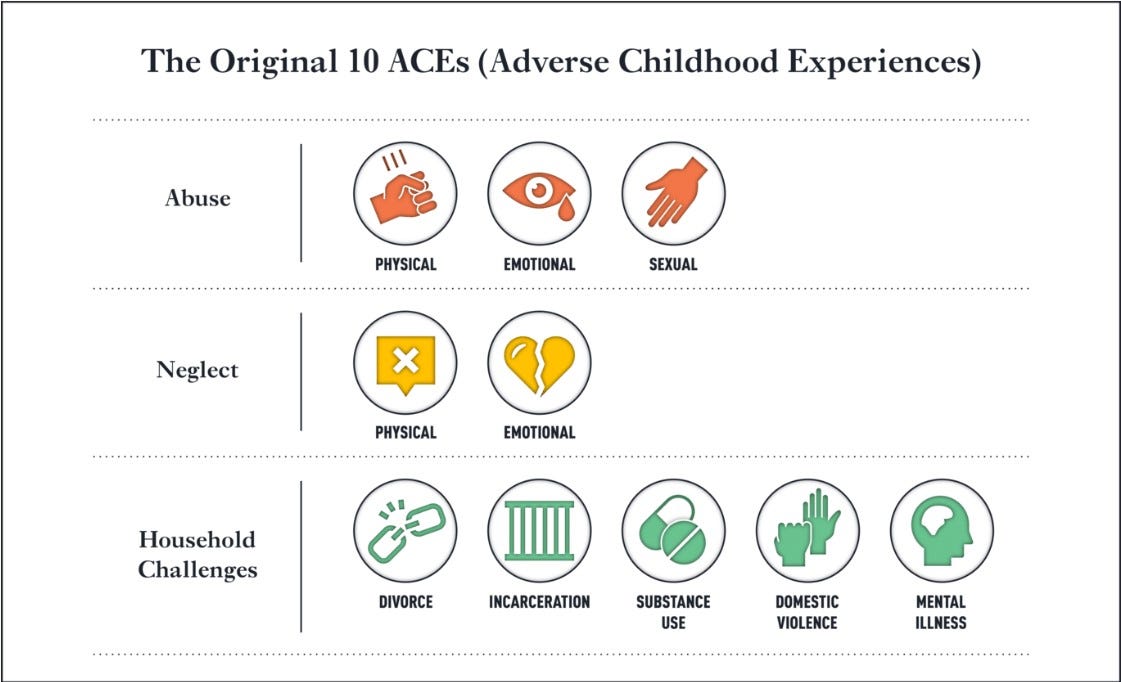

Maybe because I had my share of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), I have always worried about my students who endured major stressors beyond the inherent vulnerabilities of childhood. As a new teacher, I was sometimes overwhelmed by the burdens students carried into our classroom. Over the years, I have sought to understand the impact of adverse experiences in my students’ lives and learn how I might best help. Though some ACEs are acute, others can accumulate over time.

At times, the danger a student faced was acute and obvious:

A seventh-grade boy reached out via Teams one night to tell me his father had locked him out of the house after hitting and cursing him.

A tenth-grade girl disclosed she was living in a horse shed with no running water; the night before, her father had beaten her and left her fearing for her life if she returned home.

An eighth-grade girl revealed that a bully new to the school had spread explicit photos and rumors.

In cases like these, I knew I had to take immediate action. Knowing that well-meaning help can have unintended consequences, I learned to move mindfully: communicating with the child, getting other trusted adults involved, making reports, and staying with the situation until it was (at least temporarily) resolved.

But more often, a student was buckling under the strain of sustained, low-grade threats, what the ACE Resource Network categorizes as “beyond the 10 ACEs.”

My students have confided many stories in which these relentless stressors played a major part:

An eighth-grade girl came to me during lunch to ask what she and her mother should do about her alcoholic father.

A ninth-grade boy had to move out of town with his mom during the pandemic after a severe freeze burst their pipes. For months, they lived in a trailer on a relative’s property. Often, he was unable to complete his work since he had little internet access and had to care for his little cousins.

A seventh-grade girl panicked when she received less than an A. She was frightened to bring home a B, knowing her parents would berate and punish her as their parents had done.

An eighth-grade boy had been forced to leave his previous school because of racist bullying. He reacted angrily upon hearing quiet, bigoted comments about slavery from his new classmates during history class. His teacher kicked him out of class.

What Can Help

Every situation is unique, depending on the student, the family, the campus, our position, and available resources. But I have found certain moves to be generally helpful.

Offer Calm Empathy. When I learn a student is dealing with major stressors, I try to hold their experience in my heart with calm empathy. Though I’ve not endured what some of my students had to cope with, I know what it means to carry family secrets, to wrestle with shame and depression, to experience bullying and isolation. Within the boundaries of the student-educator relationship, I try to listen, seek to understand, and treat the student’s particular burden with respect and care, avoiding assumptions, glib reassurances, and overgeneralizations.

Honor and Strengthen Protective Factors. It can be tempting to pity students who experience resource insecurity and chaotic home lives, but children often have an intricate web of personal, family, school, community, and cultural resources from which they draw. I seek to be an ally in calling upon and thickening those protective factors and, in the process, help my students build up their reservoir of resilience and self-worth. I intentionally work to view my students as strong, resourceful people, and help them to see themselves this way too.

Study Examples of Resilience. As a social studies and ELA/R teacher, I worked to surround my students with culturally and experientially relevant stories of thriving and overcoming. When we study real or imagined examples of courage and endurance—whether in poems, histories, documentaries, short stories, essays, memoirs, or novels—our students can be encouraged by the extraordinary resilience of the human spirit. Students can also learn from overcomers in their own families, schools, and communities using interviews and other research tools.

Tap Other Allies. Usually, when I am concerned about a student’s well-being, I share with an adult at school whom I trust. In every role, I’ve sought out world-wise, well-trained, and compassionate helpers—I lean on their wisdom in these cases. I seek students’ permission to disclose particulars; if they are uncomfortable with this, and I judge the situation to not be acute, I may share the general outlines of the situation. Over time, my goal is to help build up the student’s support network. A well-trained school staff can wrap around a family struggling with insufficient resources and help relieve some of the pressure. An effective grade-level team can reframe a student’s struggles, helping to soften harsh parental judgment. A great school counselor can help a student build self-nurturing and self-advocacy practices. Often, involving the family is appropriate, but I remain mindful of how an unwanted disclosure can further endanger the child.

Default to Kindness. No matter what we do as educators, the dull ache of poverty, food and housing insecurity, neighborhood violence, and intergenerational trauma often remains. These subtle pressures can begin to grind a child’s spirit down. If a student begins to withdraw or act out under such pressure, educators sometimes pile on with judgments, words, and actions that have unintended consequences. In any conversation with or about a child, or when contemplating next steps, I can choose to practice compassion, respect, and kindness.

“Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a battle you know nothing about.”

- Wendy Mass (paraphrasing Ian Maclaren)

In personal news!

My book Making Deep Sense of Informational Texts is now available for pre-order through my Solution Tree author page and Amazon author page! It is mind-boggling to me that the legendary Cris Tovani is writing the forward!

I would be grateful for your help! Visiting my author pages, bookmarking, and sharing with your colleagues would mean so much!

For More About Supporting Students Under Stress:

Book Recommendation

In her 2021 book Equity-Centered Trauma-Informed Education, Alex Shevrin Venet offers practical steps teachers and school leaders can take to shift practice, pedagogy, and policy so that their schools serve as a protective factor for children rather than exacerbating the inequities that heighten trauma.

Other Resources

American Society for the Positive Care of Children (SPCC) (2024). We All Have a Number Story. https://americanspcc.org/number-story/

Honig, R., & Madalyn, M. (n.d.) ParentPowered. Protective Factors Framework in Practice: How a Trauma-Informed Approach Strengthens Families. https://parentpowered.com/blog/trauma-informed-education/protective-factors-framework/

National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments (2024). Protective Factors. https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/training-technical-assistance/education-level/early-learning/protective-factors

U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) (2024). About Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). https://www.cdc.gov/aces/about/index.html

Youth.gov (n.d.). Risk and Protective Factors for Youth. https://youth.gov/youth-topics/youth-mental-health/risk-and-protective-factors-youth